Q&A with Tony Kaye at D&AD

Tony Kaye Hunger Magazine

Best of Tribeca: The Heartbreaking Rise of the House of Kaye, Scallywag and Vagabond, Apr ‘11

Interview with Lake of Fire Filmmaker Tony Kaye, About.com Sept ‘07

‘I did abominable things’ The Telegraph, Jun ‘07

A quck chat with Tony Kaye, kamera.co.uk Sept ‘98

Too big for his ads? Profile: The Independant, 1996Share:

![]()

25 Feb 2013

The road that leads into the hills above Los Angeles towards the home of director Tony Kaye has as many twists to it as does the tale of the man in question. Over more than 30 years of image- making he has been decorated, derided, dubbed both genius and madman – with many of the most extreme proclamations of his abilities (both good and bad) coming from himself. Were it not for Sat Nav, you might never find his place at all. An appropriate location perhaps for one whose life seems to have been lived – for better or worse – without a map, but who has nonetheless ascended to and remains in an elevated position, even if the vision that brought him here was matched at times by an equal flair for disaster.

On arrival the view is spectacular, but there is one truth that confronts those that inhabit such regions, and it’s a fact that Kaye perhaps knows better than many of his neighbours – after all the kinks and bends of the upward journey, it takes only a moment to fall.

At the end of the 80s, Tony Kaye’s work became embedded in the British psyche when – this being the era of four-channel television and fewer digital distractions – he made a series of advertisements widely regarded as the most memorable of their time. His finesse for turning potentially mundane matters (British Rail, Real Fires and Dunlop Tyres) into arresting, admired and even mysterious pieces of short cinema earned him more awards than anyone in the industry before or since.

Kaye – who also works as his own cinematographer – came to America in the early 90s to make movies. His first, American History X, appeared in 1998 and saw its lead, Edward Norton, nominated for an Oscar. His second feature, Detachment, arrived just this year. In the intervening period he made a documentary (which took 16 years to assemble), Lake of Fire, which was also shortlisted for an Oscar, and shot videos, including one for Johnny Cash that would win a Grammy.

These, however, are simply the perceived highs of a career cardiograph with more peaks, troughs and flatlines than sanity or survival might ordinarily sustain, but which in the end, proves to be ample testament to both. Between his conspicuous successes, Kaye acquired a reputation for havoc and self sabotage that, even at its most jaw- droppingly bizarre, betrayed traces of the same unrivalled imagination that informed his triumphs.

No one is more aware of all this than he is. Someone, possibly himself, has tattooed the word “idiot” on his forearm with what looks like more angst than artistry. “Preposterous” is a term he uses a lot in reference to his past, although he also sees his crooked path as essential to his survival. “Being successful at that point,” he says of the late-90s (a period that would see him embroiled in what’s been referred to as ‘the most ludicrous legal battle Hollywood has ever seen’) “would have been the worst thing that could have happened to me. I would not be here now. There is no question. I would be in the ground.”

Such is the volume of anecdotes about him that an actual meeting brings with it a certain amount of trepidation – which is really a good thing, almost an old-fashioned sensation in an age when most Hollywood interviews are micro-managed formalities conceived and controlled to fit into a wider and equally manipulated process of PR.

Any hopes or fears that contemporary contact might entail some of the psychodramas that distinguished his famous meetings of the past (bringing a rabbi, a Catholic priest and a specially flown-in Tibetan monk to a sit down with the producers of American History X being perhaps the most notorious; persistently dressing as Osama Bin Laden in New York in the aftermath of 9/11, a debateable second) are defused by an email exchange that suggests a man driven more by an anxiety to create rather than an instinct to confront.

His latest film, Detachment, also speaks of a director who is attracting talent and generating possibilities – it could not have existed otherwise. With a tiny budget and a limited time frame it not only looks and feels like a more substantially underwritten production – “I shot it in 15 minutes and I made it look like a couple of hours,” he says – it also contains, around a powerful central performance from Adrien Brody, some remarkable work from a conspicuously gifted supporting cast including James Caan, Christina Hendricks, Lucy Liu, Blythe Danner, Marcia Gay Harden and Bryan Cranston. Finally, it seems his prior reputation for off-screen drama is being superseded by his renown as an actor’s director and a person who can get things done. “At last,” he says, “I’m in a situation where I am warm. I wouldn’t say I was hot, but I’m warm and I’m getting warmer.”

Unsurprisingly for one with such a keen eye, he is an arresting visual presence himself. With unruly grey hair, an expansive beard and studious glasses, he appears both rabbinical and piratical, which seems entirely appropriate for a man with a record of both insightful work and reckless action. He is also, necessarily perhaps, possessed of a decent sense of humour. When he comes to open the glass doors to his house and then realises he is locked inside it he smiles and nods like a man on good terms with life’s everyday conundrums.

Over a large mug of tea and a small bowl of almonds he recalls that, “I was in a dream all the time when I was at school. I distinctly remember a teacher – I think he was my French teacher. Yes. He threw the chalkboard eraser at me once and screamed at me and said, ‘I hope you can make a living staring at people and staring at things because I cannot imagine you could ever hold down any other form of job.’ So that’s what I ended up doing, because directing is just really staring at things and saying, ‘What about that?’ or, ‘What about this?’”

Kaye was born and raised in London and you can still hear it in his voice. He is a determined but occasionally hesitant speaker. Less, it seems, as a consequence of a speech impediment so pronounced in his youth that he would pre-record himself saying, “Hello, this is Tony” simply so he could use the phone, and more, one feels, because he is determined to get what he is saying straight in his own mind.

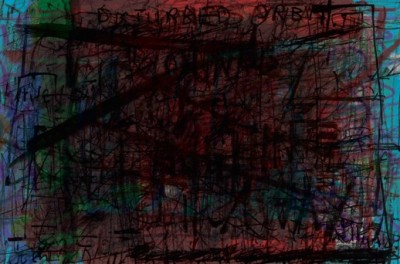

At times his speech feels as though it has been pressed into service by a flight of ideas that are not necessarily best served by language. Further to this, his house, which covers a considerable area, is strewn with paintings at various stages of completion, some of which look as if completion might never come. One canvas he shows me is so heavy with paint I can barely hold it. He shakes his head as he passes it to me, as though the urge to keep adding to it were baffling even to himself.

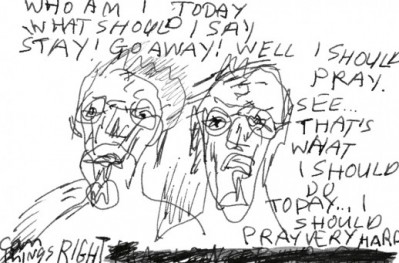

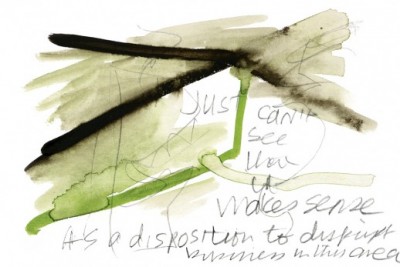

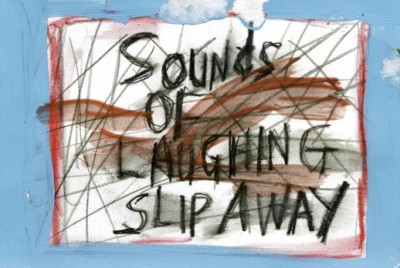

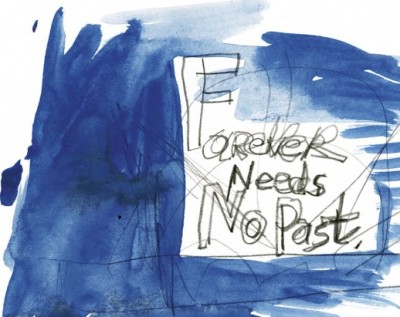

While we talk he energetically fills index cards with sketches, words and patterns in ink and paint – occasionally pausing to ask for a title, then beginning another, some of which are the images that accompany this piece.

He traces the nature and scope of his directorial ambitions to some spectacular beginnings. “My father took me to all the big biblical epics when I was a kid and I was really blown away by them, particularly The Ten Commandments when the Red Sea opened. I was also, maybe wrongly so, particularly blown away by the fact that Cecil B. DeMille came out at the beginning and spoke about the movie. I thought that was great. When I went to art school Stanley Kubrick came in. I was only 16. He had just done 2001. He came into the school and he gave a talk and I had a chat with him. I normally don’t do that and we talked for a bit, actually. I had another experience. When I left that school about a year later, I went travelling.”

Making his way along what was known at the time as the Hippy Trail, Kaye was in Israel in 1973 when he landed a labouring job working on Billy Two Hats, a Gregory Peck western being filmed by Ted Kotcheff (who would later make First Blood). It was here that Tony, whose life would go on to contain what he has often referred to as “wilderness periods”, would witness his very own miracle in the desert.

“So I am 17, humping about all these things. All of a sudden this bloke says, ‘Okay, I want a bush right there.’ Some other bloke said, ‘We’re in the middle of a desert. We can’t get your bush.’ He said, ‘I fucking want a bush right there.’ He said, ‘I will have to drive for hours.’ ‘Get me a bush. I want it right there.’ So the bloke goes off and we carry on and it starts to get dark.

“So a little bit later, it is getting really cold at night, in the middle of the desert. So the same bloke says, ‘I’m freezing. Get me a jacket. Drive into town and get me a fucking jacket.’ So some other guy goes off. I said, ‘Who is that bloke? What does he do?’ ‘Oh he is the director.’ So I thought to myself, ‘That’s the job I want. That’s the job. That’s definitely the job.’”

Total: 0